Mitochondrial Function, ATP Production

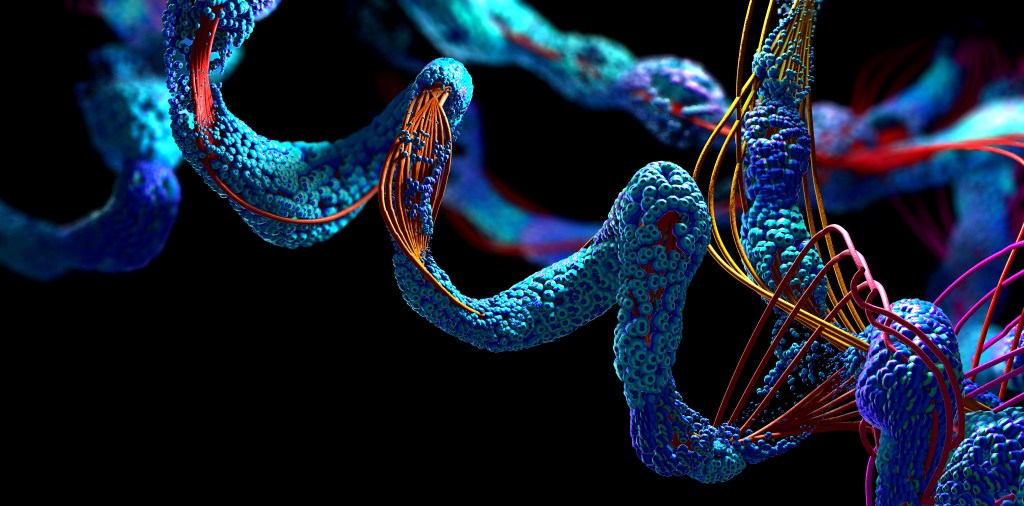

Protein Folding & Molecular Hydrogen

Written by David Guez & Jim Wilson

30 August 2022

30 August 2022

Foreword by Jim Wilson

Homeostasis, balance and functioning at ease are what a biological organism or solution requires, and for it to be able to do that, it needs the appropriate resources to be available. If these resources are not available, then the biological organism will experience dis-ease and imbalance, which will ultimately progress to stress that the body will try to rectify, usually with a less efficient backup system. The key to evolution and survival as a species has a lot to do with the availability of these such backup systems. However, returning to homeostasis and the ability to function at ease is still required by the organism should long-term survival be assured.

When it comes to life on our planet, virtually all of it relies on an organelle called the mitochondria. This is the energy conversion device cells use to convert chemical energy to biological energy, which is called Adenosine TriPhosphate or ATP for short. Some cells contain only a few mitochondria to enable enough energy to be created for the necessary cellular process to function as intended, whereas other cells that require more energy may have thousands of them. Either way, if too little energy is produced in the cell, compensatory mechanisms are engaged, including prioritizing the available energy. This means that jobs do not get done or can be done poorly, which in turn means stress, failure and repair.

Herein lies the answers we seek when trying to address the many metabolic challenges we and other species face. This high-level paper attempts not only to identify how this energy conversion takes place inside the mitochondria but to identify and understand what this energy (ATP) does and what consequences may result from a shortfall or disruption of availability when challenges arise.

ATP

How ATP is Produced in the Mitochondria

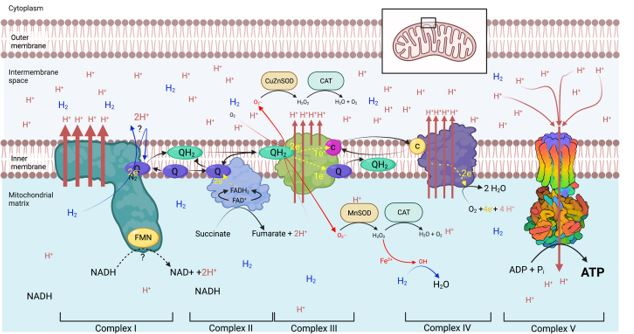

The Respiration Chain

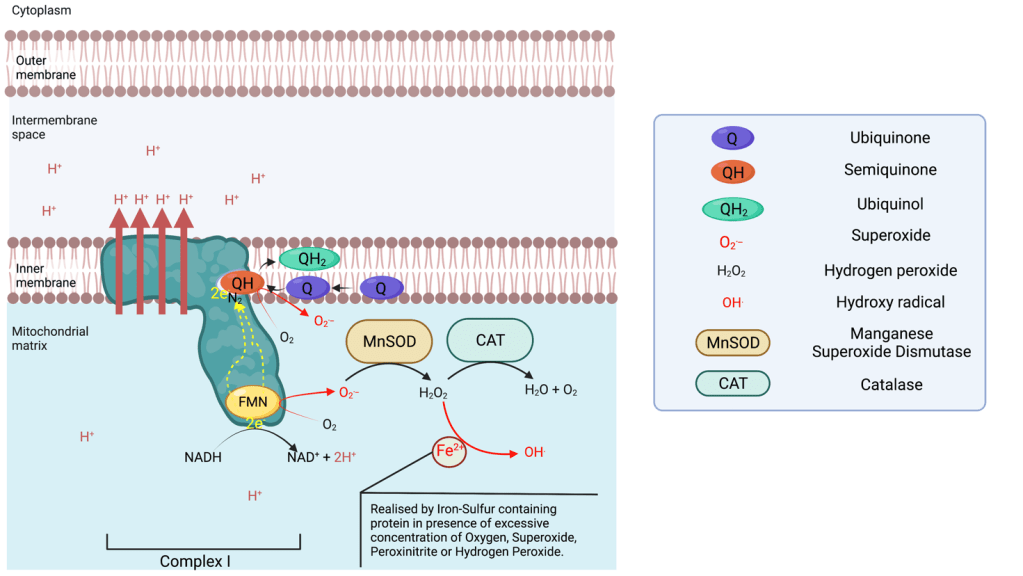

Complex I

Complex I is able to leak electrons at two sites6 and transfer them to Oxygen forming superoxide ions (O.–) during the transfer of electrons from the NADH oxidase to the N2 cluster. The superoxide produced is found in the matrix, which can be converted in the matrix to hydrogen peroxide via a manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD). Complex I is the main source of ROS in the respiratory chain. If the production of superoxide is not balanced out by the activity of MnSOD, superoxide can deactivate complex I7.

Complex II

Complex III

Complex IV

The ATP Synthase

The Action of Molecular Hydrogen on the Respiratory Chain

ATP - Beyond Energy

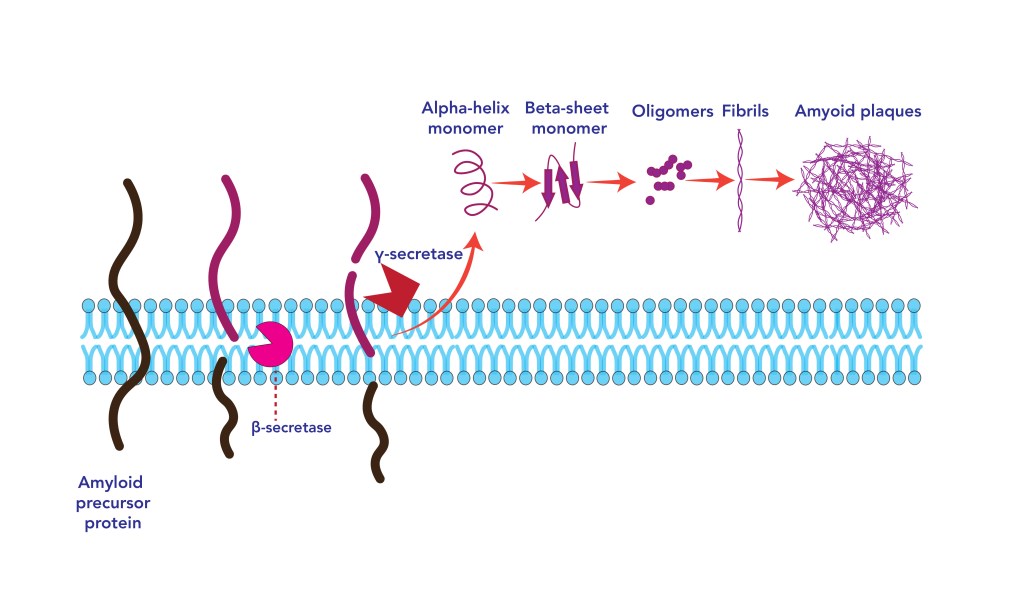

Proteins are chains of amino acids that are elongated by ribosomes in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), based on the sequence of messenger ARN. Although the precise sequence of amino acids is essential to the protein function, its correct tri-dimensional structure is critical for the fulfilment of its biological function. The tri-dimensional structure is dependent on the appropriate protein folding. Protein folding occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and is known to involve protein chaperones that facilitate the folding often using ATP as energy to promote a specific shape. However, it is only a small aspect of the folding process. Most importantly, ATP induces folding, inhibits aggregation and increases protein stability post folding12,13.

The Folding Process

The Unfolded Protein Response

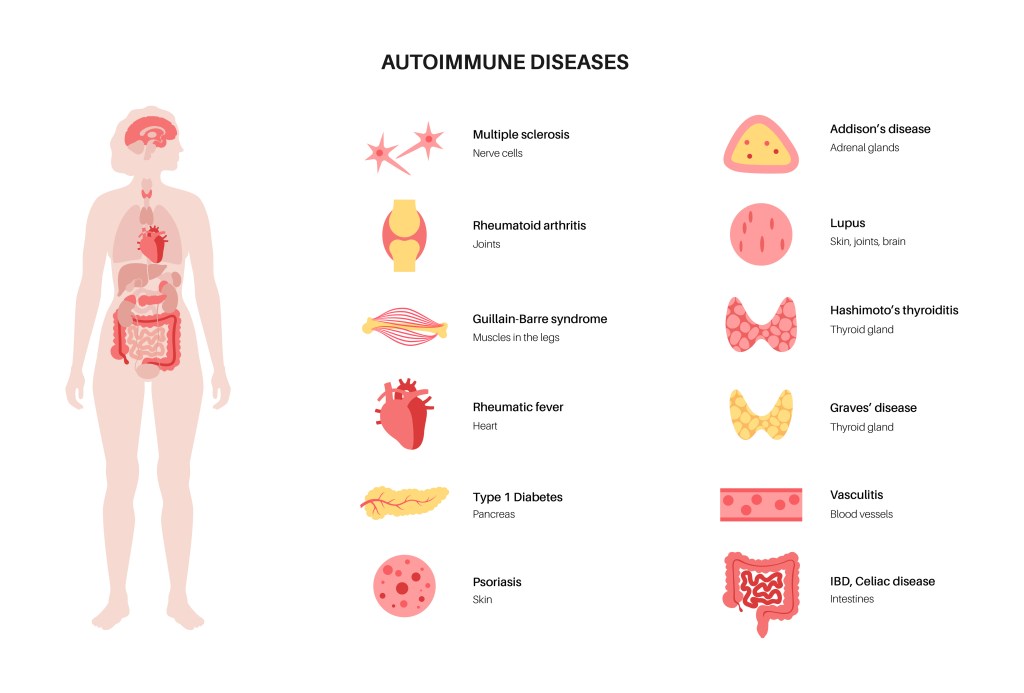

Folding and Autoimmune Disease

Folding and COVID-19

Long COVID

ER stress and Protein misfolding have been identified in numerous diseases:

- Alzheimer disease.

- Parkinson disease.

- Spinocerebellar ataxia.

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

- Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies.

- Multiple tauopathies.

- Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy.

- Fronto temporal dementia.

- Corticobasal degeneration.

- Progressive supra nuclear palsy.

- Dementia with Lewy bodies.

- Inflammatory myopathies.

- Microscopic polyangiitis.

- Rheumatoid arthritis.

And Third – during Coronavirus infections24–26 such as:

- SARS-CoV.

- Murine hepatitis virus (MHV).

- Alphacoronavirus transmisible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV).

- Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV).

Autism (as an example)

Molecular Hydrogen

Molecular hydrogen supplementation has also demonstrated its anti-inflammatory potential by down-regulating NF- kb57 (the transcription factor responsible for the production of cytokine following the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR).

An increased provision of ATP to the ER is predicted to facilitate correct protein folding by:

- Providing the energy necessary for the correct functioning of the protein chaperone.

- Promoting correct initial folding by itself13.

- Protecting the ER from the aggregation of misfiled protein13, thus decreasing the risk of ER stress.

- Preventing a run-away inflammatory response that increases the risk of developing an autoimmune response.

Thus the action of molecular hydrogen is predicted to significantly suppress the causes leading to ASD as shown in an animal model58, including associated depressive boot since molecular hydrogen has proven potential in this area59,60. Furthermore, Hydrogen supplementation could alleviate coronavirus-induced ER stress by increasing mitochondrial ATP production11 as suggested by the observed improvement in COVID-19 patients during a recent clinical trial61. More generally, Hydrogen supplementation may be a path forward to alleviate ER stress and the UPR response in a wide variety of diseases and pre-diseases.

Research funding is sought.

There are solutions.

Please Support Us.

Somtimes the correct folding of proteins just needs a helping hand.

References:

1. Epstein, T., Xu, L., Gillies, R. J. & Gatenby, R. A. Separation of metabolic supply and demand: aerobic

glycolysis as a normal physiological response to fluctuating energetic demands in the membrane. Cancer Metab 2, 7

(2014). PMID:24982758; http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2049-3002-2-7

2. Rodenburg, R. J. Mitochondrial complex I-linked disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1857, 938-945 (2016).

PMID:26906428; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.02.012

3. Bridges, H. R. et al. Structure of inhibitor-bound mammalian complex I. Nat Commun 11, 5261 (2020).

PMID:33067417; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18950-3

4. Zhu, J., Vinothkumar, K. R. & Hirst, J. Structure of mammalian respiratory complex I. Nature 536, 354-358

(2016). PMID:27509854; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature19095

5. Zhang, X. C. & Li, B. Towards understanding the mechanisms of proton pumps in Complex-I of the respiratory

chain. Biophysics Reports 5, 219-234 (2019). 10.1007/s41048-019-00094-7

6. Zhao, R. Z., Jiang, S., Zhang, L. & Yu, Z. B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and

uncoupling (Review). Int J Mol Med 44, 3-15 (2019). PMID:31115493; http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2019.4188

7. Indo, H. P. et al. A mitochondrial superoxide theory for oxidative stress diseases and aging. J Clin Biochem

Nutr 56, 1-7 (2015). PMID:25834301; http://dx.doi.org/10.3164/jcbn.14-42

8. Dourado, D. F. A. R., Swart, M. & Carvalho, A. T. P. Why the Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD) Cofactor

Needs To Be Covalently Linked to Complex II of the Electron-Transport Chain for the Conversion of FADH2 into FAD.

Chemistry 24, 5246-5252 (2018). PMID:29124817; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.201704622

9. Ishihara, G., Kawamoto, K., Komori, N. & Ishibashi, T. Molecular hydrogen suppresses superoxide generation

in the mitochondrial complex I and reduced mitochondrial membrane potential. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 522,

965-970 (2020). PMID:31810604; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.11.135

10. Zhang, X. et al. Hydrogen evolution and absorption phenomena in plasma membrane of higher plants.

(2020). 10.1101/2020.01.07.896852

11. Gvozdjáková, A. et al. A new insight into the molecular hydrogen effect on coenzyme Q and mitochondrial

function of rats. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 98, 29-34 (2020). 10.1139/cjpp-2019-0281

12. Ou, X. et al. ATP Can Efficiently Stabilize Protein through a Unique Mechanism. JACS Au 1, 1766-1777 (2021).

PMID:34723279; http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.1c00316

13. Kang, J., Lim, L. & Song, J. ATP induces protein folding, inhibits aggregation and antagonizes destabilization

by effectively mediating water-protein-ion interactions, the heart of protein folding and aggregation. bioRxiv (2020).

10.1101/2020.06.21.163758

14. Alaei, L., Ashengroph, M. & Moosavi-Movahedi, A. A. The concept of protein folding/unfolding and its

impacts on human health. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 126, 227-278 (2021). PMID:34090616;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.apcsb.2021.01.007

15. Halperin, L., Jung, J. & Michalak, M. The many functions of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperones and

folding enzymes. IUBMB Life 66, 318-326 (2014). PMID:24839203; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/iub.1272

16. Stull, F., Koldewey, P., Humes, J. R., Radford, S. E. & Bardwell, J. C. A. Substrate protein folds while it is bound

to the ATP-independent chaperone Spy. Nat Struct Mol Biol 23, 53-58 (2016). PMID:26619265;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3133

17. Balsa, E. et al. ER and Nutrient Stress Promote Assembly of Respiratory Chain Supercomplexes through the

PERK-eIF2α Axis. Mol Cell 74, 877-890.e6 (2019). PMID:31023583; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.031

18. Schröder, M. & Kaufman, R. J. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem 74, 739-789

(2005). PMID:15952902; http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134

19. Bettigole, S. E. & Glimcher, L. H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 33, 107-138

(2015). PMID:25493331; http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112116

20. Arase, N. & Arase, H. Cellular misfolded proteins rescued from degradation by MHC class II molecules are

possible targets for autoimmune diseases. J Biochem 158, 367-372 (2015). PMID:26381536;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jb/mvv093

21. Hiwa, R. & Arase, H. Misfolded proteins complexed with MHC class II molecules are targets for

autoantibodies. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi 39, 78-83 (2016). PMID:27181239;

http://dx.doi.org/10.2177/jsci.39.78

22. Arase, H. Rheumatoid Rescue of Misfolded Cellular Proteins by MHC Class II Molecules: A New Hypothesis

for Autoimmune Diseases. Adv Immunol 129, 1-23 (2016). PMID:26791856;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.ai.2015.09.005

23. Junjappa, R. P., Patil, P., Bhattarai, K. R., Kim, H. R. & Chae, H. J. IRE1α Implications in Endoplasmic Reticulum

Stress-Mediated Development and Pathogenesis of Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol 9, 1289 (2018).

PMID:29928282; http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01289

24. Versteeg, G. A., van de Nes, P. S., Bredenbeek, P. J. & Spaan, W. J. The coronavirus spike protein induces

endoplasmic reticulum stress and upregulation of intracellular chemokine mRNA concentrations. J Virol 81, 10981-

10990 (2007). PMID:17670839; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01033-07

25. Xue, M. et al. The PERK Arm of the Unfolded Protein Response Negatively Regulates Transmissible

Gastroenteritis Virus Replication by Suppressing Protein Translation and Promoting Type I Interferon Production. J

Virol 92, e00431-18 (2018). PMID:29769338; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00431-18

26. Echavarría-Consuegra, L. et al. Manipulation of the unfolded protein response: A pharmacological strategy

against coronavirus infection. PLoS Pathog 17, e1009644 (2021). PMID:34138976;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1009644

27. Chan, C. P. et al. Modulation of the unfolded protein response by the severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus spike protein. J Virol 80, 9279-9287 (2006). PMID:16940539; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00659-06

28. Ye, Z., Wong, C. K., Li, P. & Xie, Y. A SARS-CoV protein, ORF-6, induces caspase-3 mediated, ER stress and JNK-

dependent apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1780, 1383-1387 (2008). PMID:18708124;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.07.009

29. Minakshi, R. et al. The SARS Coronavirus 3a protein causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and induces ligand-

independent downregulation of the type 1 interferon receptor. PLoS One 4, e8342 (2009). PMID:20020050;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0008342

30. Sung, S. C., Chao, C. Y., Jeng, K. S., Yang, J. Y. & Lai, M. M. The 8ab protein of SARS-CoV is a luminal ER

membrane-associated protein and induces the activation of ATF6. Virology 387, 402-413 (2009). PMID:19304306;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.021

31. Shi, C. S., Nabar, N. R., Huang, N. N. & Kehrl, J. H. SARS-Coronavirus Open Reading Frame-8b triggers

intracellular stress pathways and activates NLRP3 inflammasomes. Cell Death Discov 5, 101 (2019). PMID:31231549;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41420-019-0181-7

32. Xue, M. & Feng, L. The Role of Unfolded Protein Response in Coronavirus Infection and Its Implications for

Drug Design. Front Microbiol 12, 808593 (2021). PMID:35003039; http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.808593

33. Schniertshauer, D., Gebhard, D. & Bergemann, J. Age-Dependent Loss of Mitochondrial Function in Epithelial

Tissue Can Be Reversed by Coenzyme Q10. J Aging Res 2018, 6354680 (2018). PMID:30254763;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2018/6354680

34. Omori, R., Matsuyama, R. & Nakata, Y. The age distribution of mortality from novel coronavirus disease

(COVID-19) suggests no large difference of susceptibility by age. Sci Rep 10, 16642 (2020). PMID:33024235;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73777-8

35. Wu, J. T. et al. Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China. Nat

Med 26, 506-510 (2020). PMID:32284616; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0822-7

36. Nunn, A. V. W. et al. SARS-CoV-2 and mitochondrial health: implications of lifestyle and ageing. Immun

Ageing 17, 33 (2020). PMID:33292333; http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12979-020-00204-x

37. Ajaz, S. et al. Mitochondrial metabolic manipulation by SARS-CoV-2 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of

patients with COVID-19. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 320, C57-C65 (2021). PMID:33151090;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00426.2020

38. Zimmermann, R. & Lang, S. A Little AXER ABC: ATP, BiP, and Calcium Form a Triumvirate Orchestrating

Energy Homeostasis of the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Contact 3, 251525642092679 (2020).

10.1177/2515256420926795

39. Frere, J. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters and humans results in lasting and unique systemic

perturbations post recovery. Sci Transl Med eabq3059 (2022). PMID:35857629;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abq3059

40. Lauro, C. & Limatola, C. Metabolic Reprograming of Microglia in the Regulation of the Innate Inflammatory

Response. Front Immunol 11, 493 (2020). PMID:32265936; http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00493

41. Niu, Y. et al. Hydrogen Attenuates Allergic Inflammation by Reversing Energy Metabolic Pathway Switch. Sci

Rep 10, 1962 (2020). PMID:32029879; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58999-0

42. Soto, C. & Estrada, L. D. Protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Arch Neurol 65, 184-189 (2008).

PMID:18268186; http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2007.56

43. Sweeney, P. et al. Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases: implications and strategies. Transl

Neurodegener 6, 6 (2017). PMID:28293421; http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40035-017-0077-5

44. Soto, C. & Pritzkow, S. Protein misfolding, aggregation, and conformational strains in neurodegenerative

diseases. Nat Neurosci 21, 1332-1340 (2018). PMID:30250260; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0235-9

45. Hiwa, R. et al. Myeloperoxidase/HLA Class II Complexes Recognized by Autoantibodies in Microscopic

Polyangiitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 69, 2069-2080 (2017). PMID:28575531; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.40170

46. Arase, N. et al. Cell surface-expressed Ro52/IgG/HLA-DR complex is targeted by autoantibodies in patients

with inflammatory myopathies. J Autoimmun 126, 102774 (2022). PMID:34896887;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102774

47. Yamamoto, W. R. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress alters ryanodine receptor function in the murine

pancreatic β cell. J Biol Chem 294, 168-181 (2019). PMID:30420428; http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA118.005683

48. Ii Timberlake, M. & Dwivedi, Y. Linking unfolded protein response to inflammation and depression: potential

pathologic and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry 24, 987-994 (2019). PMID:30214045;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0241-z

49. Edmiston, E., Ashwood, P. & Van de Water, J. Autoimmunity, Autoantibodies, and Autism Spectrum

Disorder. Biol Psychiatry 81, 383-390 (2017). PMID:28340985; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.031

50. Onore, C., Careaga, M. & Ashwood, P. The role of immune dysfunction in the pathophysiology of autism.

Brain Behav Immun 26, 383-392 (2012). PMID:21906670; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2011.08.007

51. Frye, R. E. & Rossignol, D. A. Mitochondrial dysfunction can connect the diverse medical symptoms

associated with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Res 69, 41R-7R (2011). PMID:21289536;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e318212f16b

52. De Jaco, A. et al. A mutation linked with autism reveals a common mechanism of endoplasmic reticulum

retention for the alpha,beta-hydrolase fold protein family. J Biol Chem 281, 9667-9676 (2006). PMID:16434405;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M510262200

53. De Jaco, A., Comoletti, D., King, C. C. & Taylor, P. Trafficking of cholinesterases and neuroligins mutant

proteins. An association with autism. Chem Biol Interact 175, 349-351 (2008). PMID:18555979;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.023

54. Fujita, E. et al. Autism spectrum disorder is related to endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by mutations in

the synaptic cell adhesion molecule, CADM1. Cell Death Dis 1, e47 (2010). PMID:21364653;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2010.23

55. Trobiani, L. et al. The neuroligins and the synaptic pathway in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neurosci Biobehav

Rev 119, 37-51 (2020). PMID:32991906; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.017

56. Ulbrich, L. et al. Autism-associated R451C mutation in neuroligin3 leads to activation of the unfolded protein

response in a PC12 Tet-On inducible system. Biochem J 473, 423-434 (2016). PMID:26621873;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BJ20150274

57. Ichihara, M. et al. Beneficial biological effects and the underlying mechanisms of molecular hydrogen –

comprehensive review of 321 original articles. Med Gas Res 5, 12 (2015). PMID:26483953;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13618-015-0035-1

58. Guo, Q. et al. Hydrogen-Rich Water Ameliorates Autistic-Like Behavioral Abnormalities in Valproic Acid-

Treated Adolescent Mice Offspring. Front Behav Neurosci 12, 170 (2018). PMID:30127728;

http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00170

59. Satoh, Y. The Potential of Hydrogen for Improving Mental Disorders. Curr Pharm Des 27, 695-702 (2021).

PMID:33185151; http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1381612826666201113095938

60. Zhang, Y. et al. Effects of hydrogen-rich water on depressive-like behavior in mice. Sci Rep 6, 23742 (2016).

PMID:27026206; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep23742

61. Guan, W. J. et al. Hydrogen/oxygen mixed gas inhalation improves disease severity and dyspnea in patients

with Coronavirus disease 2019 in a recent multicenter, open-label clinical trial. J Thorac Dis 12, 3448-3452 (2020).

PMID:32642277; http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-2020-057