Hydrogen Driven Agriculture

Delivered By Water

Written by David Guez & Jim Wilson

1 August 2022

Given the world’s environment and climate change potential in the coming years, along with the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, any factor that would increase organism resilience should be investigated. In this regard, Molecular Hydrogen and Oxygen supplementation offers enormous potential and should be brought to the forefront of our thinking about agriculture and food production.

Here we provide a summary of what is currently known to introduce the immense potential offered by supplementing food production systems with Oxy-hydrogen. There are many sub-categories within this enormous field, and we will further develop these specific areas as interest dictates.

Soil Fertility and Hydroxygen

Interestingly, the use of water infused with hydrogen gas without the use of fertiliser still translated to a 9.1% yield increase, compared to the group with fertiliser and standard water. Most importantly, the use of hydrogen nanobubbles also significantly improved the quality of the crop in terms of nutrient content and taste.

Finally, while Hydrogen water post-harvest treatment decreased the accumulation of nitrite in stored tomatoes12, in strawberries, the preharvest use of hydrogen nanobubble enriched water enhanced thevolatile profiles, sugar-acid ratio, and sensory attributes of the crop with and without fertiliser13. The increased production of secondary metabolites is under the control of H26,14.

Hydrogen can also indirectly enhance the plant’s resistance to stress by affecting soil microbial composition. For instance, Hydrogen gas has been demonstrated to promote the recruitment of beneficial rhizosphere aerobic beta-proteobacteria Variovorax paradoxus, that is responsible for soil regeneration following crop rotation with legumes15 (such as soybean or turnip). The Variovorax paradoxus strain has been demonstrated themselves to also protect plants from abiotic stress16, improving growth17,18 and yield.

Furthermore, V. paradoxus is known to metabolise residual pesticides19 and herbicides20 in soils, improving soil condition. Interestingly, after 7-8 days H2 gas treatment of soil, the soil starts fixating CO2 and not releasing it to the atmosphere, but taking it from the atmosphere and fixating it in the soil21. Grain planted soils are net producers of CO2 (10 million tonnes CO2-e annually in Australia). This research suggests that treatment with oxy-hydrogen enriched water may reverse this trend by increasing root system mass and increasing soil CO2 fixation, creating a carbon sink.

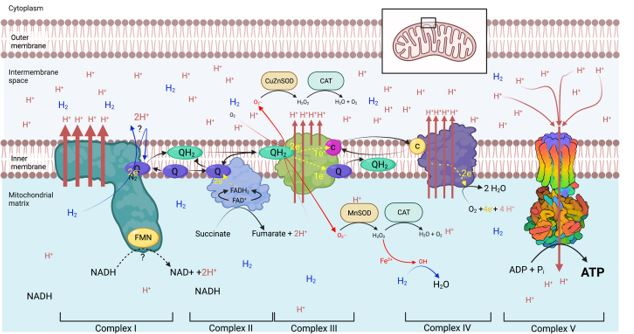

The Action of Molecular Hydrogen on the Respiratory Chain

Regardless of how H2 participates in the respiratory chain, it is demonstrated that H2 supplementation translates into a more than 50% per min increase in ATP production by the mitochondria24. An increase that appears to be a least partially to be uncoupled from nutrient intake.

An increase in ATP production by the mitochondria, following H2 supplementation, means that cells can divert the nutrients not used to produce energy, to the production of the building blocks of the cell. This explains why crops supplemented with hydrogen can invest more energy into growth and production.

Mitochondrial ATP Production and ER Stress

Molecular Hydrogen supplementation also enables an increased mitochondrial ATP production while suppressing the production of superoxide by Complex 1.

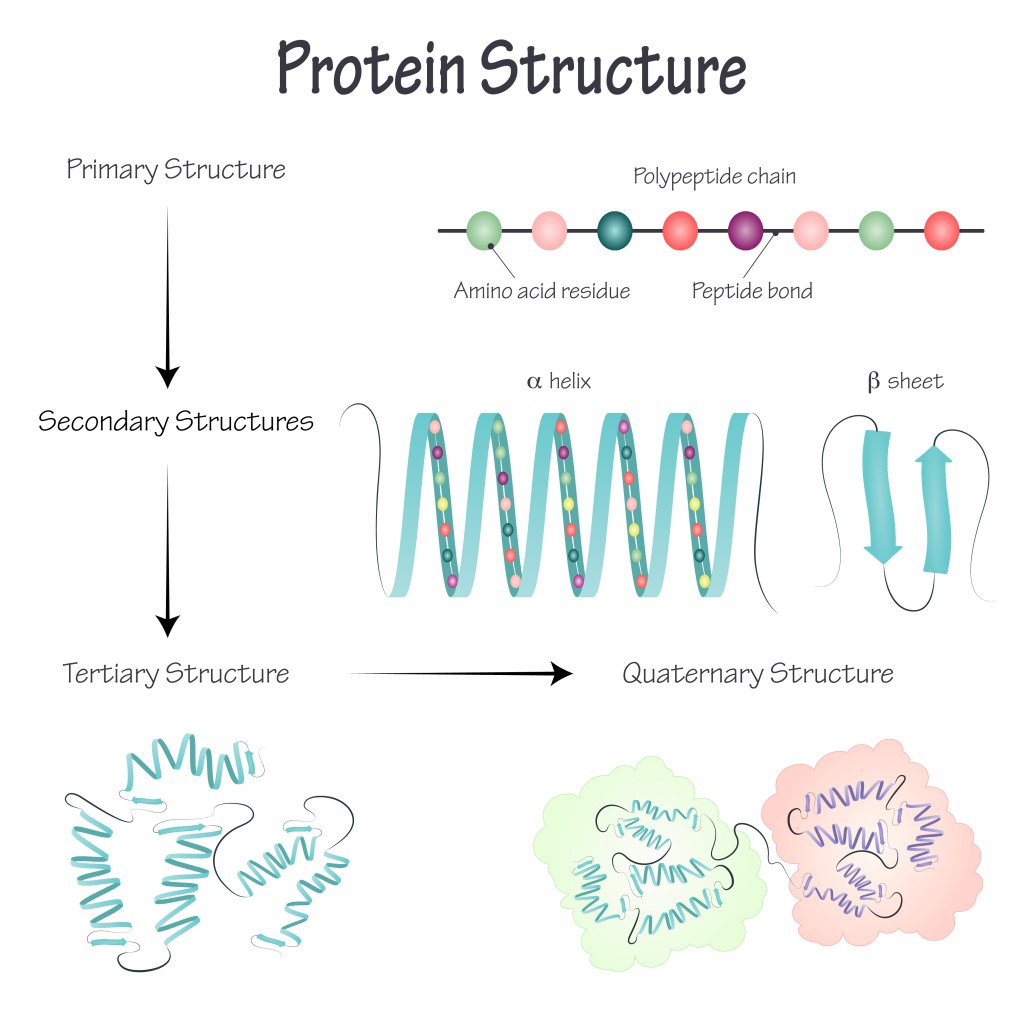

Given that ATP is necessary for the appropriate folding of proteins in the ER as a source of energy or as a co-factor27, and given that it has been shown that ATP facilitates by itself the stability and proper folding of proteins as well as prevents the aggregation of misfolded proteins28,29, we believe that the increased resistance to abiotic stress shown by plants supplemented with hydrogen is a direct consequence of an increased availability in mitochondrial ATP.

Rumen Fermentation Optimisation and Methane Emissions

It is possible to decrease cow methane emissions by manipulating the type of feed they have access to or by providing food additives that are counter to methane production however, these approaches can be costly or impractical.

Research suggests that elevating the dissolved concentration of hydrogen up to 100µM (0.2 ppm) may thermodynamically inhibit methanogenesis while favouring other pathways that produce compounds that can be assimilated by the animal and increase propionate production33,34, which is linked to better milk production and quality35, while decreasing the energy loss experienced by the animal when methane is produced. The potential Hydrogen saturation level in water between 20 and 40C is 1.6 to 1.4 ppm and is 7 to 8 times more than the upper limit of hydrogen concentration that should inhibit methanogenesis in rumens.

It is expected that Hydrogen supplementation of cows in the form of hydrogen and oxygen rich water would significantly reduce the amount of methane emission while promoting a pathway that improves food absorption by the animal, increases immune system strength and increases the overall quality of the beast. It is interesting to note that adding the oxygen to the water could also stop methanogenesis36 without affecting butyrate and propionate production which is important for milk quality.

Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

As it is known, Hydrogen supplementation decreases oxidative stress and decreases inflammation. It is important to remember that inflammation causes a redirection of nutrients from accretion in meat, milk and wool towards liver anabolism37 and thus represents a non-negligible economic cost. Thus, it is expected that hydrogen supplementation, through drinking water for example, will improve meat, milk and wool production potential.

Globally Significant

Throughout all agricultural endeavours, its potential represents a low-cost solution to improve nutritional content and enhance production under abiotic stresses, such as drought and salinity. It will enable productivity from millions of hectares of land otherwise thought lost for various reasons, as well as the ability to regenerate the environment such as is required by environmentally destructive enterprises such as mining and deforestation.

The world’s agriculture industry is valued at approximately $12 trillion dollars annually. Molecular hydrogen and oxygen availability in soil has plant growth-promoting properties that may translate to a direct 20% – 30% improvement in yield alone. Furthermore, molecular hydrogen and oxygen soil treatment will lead to further development of microbiota diversity within the soil, thus improving the overall health, fertility and disease resistance potential while promoting plant growth simultaneously. The ascendancy of bacterium further promotes the formation of complex biofilms in the soil, that in turn enables carbon sequestration into the soil from the atmosphere. This has enormous implications when considering the regeneration of lost productive farmland and can significantly ameliorate further destruction of existing stressed pastures and ecosystems.

Furthermore, as this information becomes widely accepted, we foresee that consumers of the future will want to know more about where their food has come from and that they will want Hydrogen based farming certifications in a similar fashion to what we already see in the “Organically Certified” spaces.

The technology affords significant value towards a governments’ farm biodiversity certification scheme, will set new standards around the world, and give farmers considerable advantage and preference throughout the global marketplace. It offers significant advancement for live export, red meat, white meat, seafood and plant industries while dramatically reducing waste.

Environment Regeneration

Molecular Hydrogen and Oxygen supplementation offers enormous potential and implications when considering the regeneration of lost productive farmland and can significantly ameliorate further destruction of existing stressed pastures and ecosystems. The development of this knowledge represents an ability to repair farmland thought lost for generations and will enable regeneration and the ability to resume productive farming in soils and environments not thought possible before now.

Carbon

Research into the associated relationship between mitochondria and chloroplast is expected to reveal significant efficiency improvements to both protein folding and carbon sequestration and the creation of biomass above and below the ground.

Animal Protein

- Oxygen or Hydrogen supplementation, for example, by the provision of water enrichment, improves metabolism and thus Feed conversion ratio in livestock.

- For instance, in meat chicken, the enrichment of water with oxygen or water enrichment with hydrogen, improves weight gain by at least 10% individually, and we are expecting

Delivery Method

Bubbles (In General)

In the case of soda, the CO2 was dissolved under pressure in the soda, and when you opened the bottle, the pressure dropped, allowing the excess CO2 to leave the solution and form gas bubbles. In the case of your aquarium, we are simply pushing air through a porous stone to create bubbles. Here we are trying to dissolve oxygen faster in the water to compensate for the one used by the fish and other life-forms present in the tank.

Note that we could achieve the same by increasing the surface area of the water exposed to the atmosphere. Indeed, if you think about it, each bubble we produce increases the surface area of contact between the air and the water enabling more gas exchange between air and water. Nonetheless, although we can speed up the process by increasing the surface area available for gas exchange, the maximum amount of oxygen we can dissolve in water at equilibrium is solely determined by the partial pressure of oxygen in the atmosphere and the temperature. The colder the water is, the more oxygen can dissolve in it at the same partial pressure.

Size of the Bubble

Microbubbles

Nanobubble Technology and Advancements

Therefore, the amount of oxygen or gas of interest stored in the body of water is far more substantial than the saturation level. Finally, because they are again smaller than microbubbles, the potential surface area for gas exchange is greater again. There is much anticipation for a solution that affords virtually instantaneous infusion of gasses into fluids across various industries and applications around the world. Various methods are adopted with varying levels of success with significantly different degrees of associated expense.

References

https://grdc.com.au/research/reports/report?id=3618

1. Chérif, M., Tirilly, Y. & Bélanger, R. R. Effect of oxygen concentration on plant growth, lipidperoxidation, and receptivity of tomato roots to Pythium F under hydroponic conditions. European Journal of Plant Pathology 103, 255-264 (1997). 10.1023/a:1008691226213

2. Smith, G. S., Buwalda, J. G., Green, T. G. A. & Clark, C. J. Effect of oxygen supply and temperature at the root on the physiology of kiwifruit vines. New phytologist 113, 431-437 (1989). 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1989.tb00354.x

3. Wu, Q. et al. Understanding the mechanistic basis of ameliorating effects of hydrogen rich water on salinity tolerance in barley. Environmental and Experimental Botany 177, 104136 (2020). 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104136

4. Xie, Y., Mao, Y., Lai, D., Zhang, W. & Shen, W. H(2) enhances arabidopsis salt tolerance by manipulating ZAT10/12-mediated antioxidant defence and controlling sodium exclusion. PLoS One 7, e49800 (2012). PMID:23185443; http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049800

5. Xie, Y. et al. Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Nitric Oxide Production Contributes to Hydrogen-Promoted Stomatal Closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 165, 759-773 (2014). PMID:24733882; http://dx.doi.org/10.1104/pp.114.237925

6. Xie, Y. et al. Hydrogen-rich water-alleviated ultraviolet-B-triggered oxidative damage is partially associated with the manipulation of the metabolism of (iso)flavonoids and antioxidant defence in Medicago sativa. Funct Plant Biol 42, 1141-1157 (2015). PMID:32480752; http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/FP15204

7. Wu, Q., Su, N., Cai, J., Shen, Z. & Cui, J. Hydrogen-rich water enhances cadmium tolerance in Chinese cabbage by reducing cadmium uptake and increasing antioxidant capacities. J Plant Physiol 175, 174-182 (2015). PMID:25543863; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2014.09.017

8. Su, N. et al. Hydrogen gas alleviates toxic effects of cadmium in Brassica campestris seedlings through up-regulation of the antioxidant capacities: Possible involvement of nitric oxide. Environ Pollut 251, 45-55 (2019). PMID:31071632; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.094

9. Dong, Z., Wu, L., Kettlewell, B., Caldwell, C. D. & Layzell, D. B. Hydrogen fertilization of soils–is this a benefit of legumes in rotation. Plant, Cell & Environment 26, 1875-1879 (2003). 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01103.x

10. Li, L., Zeng, Y., Cheng, X. & Shen, W. The Applications of Molecular Hydrogen in Horticulture. Horticulturae 7, 513 (2021). 10.3390/horticulturae7110513

11. Li, M. et al. Hydrogen Fertilization Improves Yield and Quality of Cherry Tomatoes Compared to the Conventional Fertilizers. SSRN Electronic Journal (2022). 10.2139/ssrn.4064621

12. Zhang, Y. et al. Nitrite accumulation during storage of tomato fruit as prevented by hydrogen gas. International Journal of Food Properties22, 1425-1438 (2019). 10.1080/10942912.2019.1651737

13. Li, L. et al. Preharvest application of hydrogen nanobubble water enhances strawberry flavor and consumer preferences. Food Chem 377, 131953 (2022). PMID:34973592; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131953

14. Zhang, X. et al. Transcriptome analysis of radish sprouts hypocotyls reveals the regulatory role of hydrogen-rich water in anthocyanin biosynthesis under UV-A. BMC Plant Biol 18, 227 (2018). PMID:30305047; http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1449-4

15. Maimaiti, J. et al. Isolation and characterization of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria induced following exposure of soil to hydrogen gas and their impact on plant growth. Environ Microbiol 9, 435-444 (2007). PMID:17222141; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01155.x

16. Tamburini, E. et al. Bioaugmentation-Assisted Phytostabilisation of Abandoned Mine Sites in South West Sardinia. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 98, 310-316 (2017). PMID:27385370; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00128-016-1866-8

17. Jiang, F. et al. Multiple impacts of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Variovorax paradoxus 5C-2 on nutrient and ABA relations of Pisum sativum. J Exp Bot 63, 6421-6430 (2012). PMID:23136167; http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers301

18. Han, J. I. et al. Complete genome sequence of the metabolically versatile plant growth-promoting endophyte Variovorax paradoxus S110. J Bacteriol193, 1183-1190 (2011). PMID:21183664; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00925-10

19. Fisher, P. R., Appleton, J. & Pemberton, J. M. Isolation and characterization of the pesticide-degrading plasmid pJP1 from Alcaligenes paradoxus. J Bacteriol 135, 798-804 (1978). PMID:690076; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/jb.135.3.798-804.1978

20. Vallaeys, T., Albino, L., Soulas, G., Wright, A. D. & Weightman, A. J. Isolation and characterization of a stable 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degrading bacterium, Variovorax paradoxus, using chemostat culture. Biotechnology letters 20, 1073-1076 (1998).

21. Dong, Z. & Layzell, D. B. H2 oxidation, O2 uptake and CO2 fixation in hydrogen treated soils. Plant and soil 229, 1-12 (2001). 10.1023/A:1004810017490

22. Ishihara, G., Kawamoto, K., Komori, N. & Ishibashi, T. Molecular hydrogen suppresses superoxide generation in the mitochondrial complex I and reduced mitochondrial membrane potential. Biochem Biophys Res Commun522, 965-970 (2020). PMID:31810604; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.11.135

23. Zhang, X. et al. Hydrogen evolution and absorption phenomena in plasma membrane of higher plants. (2020). 10.1101/2020.01.07.896852

24. Gvozdjáková, A. et al. A new insight into the molecular hydrogen effect on coenzyme Q and mitochondrial function of rats. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 98, 29-34 (2020). 10.1139/cjpp-2019-0281

25. Park, C. J. & Park, J. M. Endoplasmic Reticulum Plays a Critical Role in Integrating Signals Generated by Both Biotic and Abiotic Stress in Plants. Front Plant Sci 10, 399 (2019). PMID:31019523; http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00399

26. Reyes-Impellizzeri, S. & Moreno, A. A. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Role in the Plant Response to Abiotic Stress. Front Plant Sci 12, 755447 (2021). PMID:34868142; http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.755447

27. Liu, J. X. & Howell, S. H. Endoplasmic reticulum protein quality control and its relationship to environmental stress responses in plants. Plant Cell 22, 2930-2942 (2010). PMID:20876830; http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.110.078154

28. Kang, J., Lim, L. & Song, J. ATP induces protein folding, inhibits aggregation and antagonizes destabilization by effectively mediating water-protein-ion interactions, the heart of protein folding and aggregation. bioRxiv (2020). 10.1101/2020.06.21.163758

29. Ou, X. et al. ATP Can Efficiently Stabilize Protein through a Unique Mechanism. JACS Au 1, 1766-1777 (2021). PMID:34723279; http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.1c00316

30. Chaucheyras-Durand, F., Masséglia, S., Fonty, G. & Forano, E. Influence of the composition of the cellulolytic flora on the development of hydrogenotrophic microorganisms, hydrogen utilization, and methane production in the rumens of gnotobiotically reared lambs. Applied and environmental microbiology 76, 7931-7937 (2010). 10.1128/AEM.01784-10

31. Mitsumori, M. & Sun, W. Control of rumen microbial fermentation for mitigating methane emissions from the rumen. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 21, 144-154 (2008). 10.5713/ajas.2008.r01

32. Tseten, T., Sanjorjo, R. A., Kwon, M. & Kim, S.-W. Strategies to Mitigate Enteric Methane Emissions from Ruminant Animals. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 32, 269-277 (2022). 10.4014/jmb.2202.02019

33. Ungerfeld, E. M. Metabolic hydrogen flows in rumen fermentation: principles and possibilities of interventions. Frontiers in Microbiology 589 (2020). 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00589

34. Janssen, P. H. Influence of hydrogen on rumen methane formation and fermentation balances through microbial growth kinetics and fermentation thermodynamics. Animal Feed Science and Technology 160, 1-22 (2010). 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2010.07.002

35. Miettinen, H. & Huhtanen, P. Effects of the ratio of ruminal propionate to butyrate on milk yield and blood metabolites in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 79, 851-861 (1996). PMID:8792285; http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76434-2

36. Scott, R. I. et al. The presence of oxygen in rumen liquor and its effects on methanogenesis. Journal of Applied Bacteriology 55, 143-149 (1983). 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1983.tb02658.x

37. Colditz, I. G. Effects of the immune system on metabolism: implications for production and disease resistance in livestock. Livestock Production Science 75, 257-268 (2002). 10.1016/s0301-6226(01)00320-7